What the Bible Does and Does Not Mean by "Apocalypse" / Lo que la Biblia entiende y no entiende por «apocalipsis»

Some words have changed drastically over time. When I was growing up, “Spam” had only one meaning: it was what we ate when my mom was out of town. Now, although I’m thankful that the canned meat still exists, “spam” mostly refers to the endless stream of unwanted messages in our inboxes.

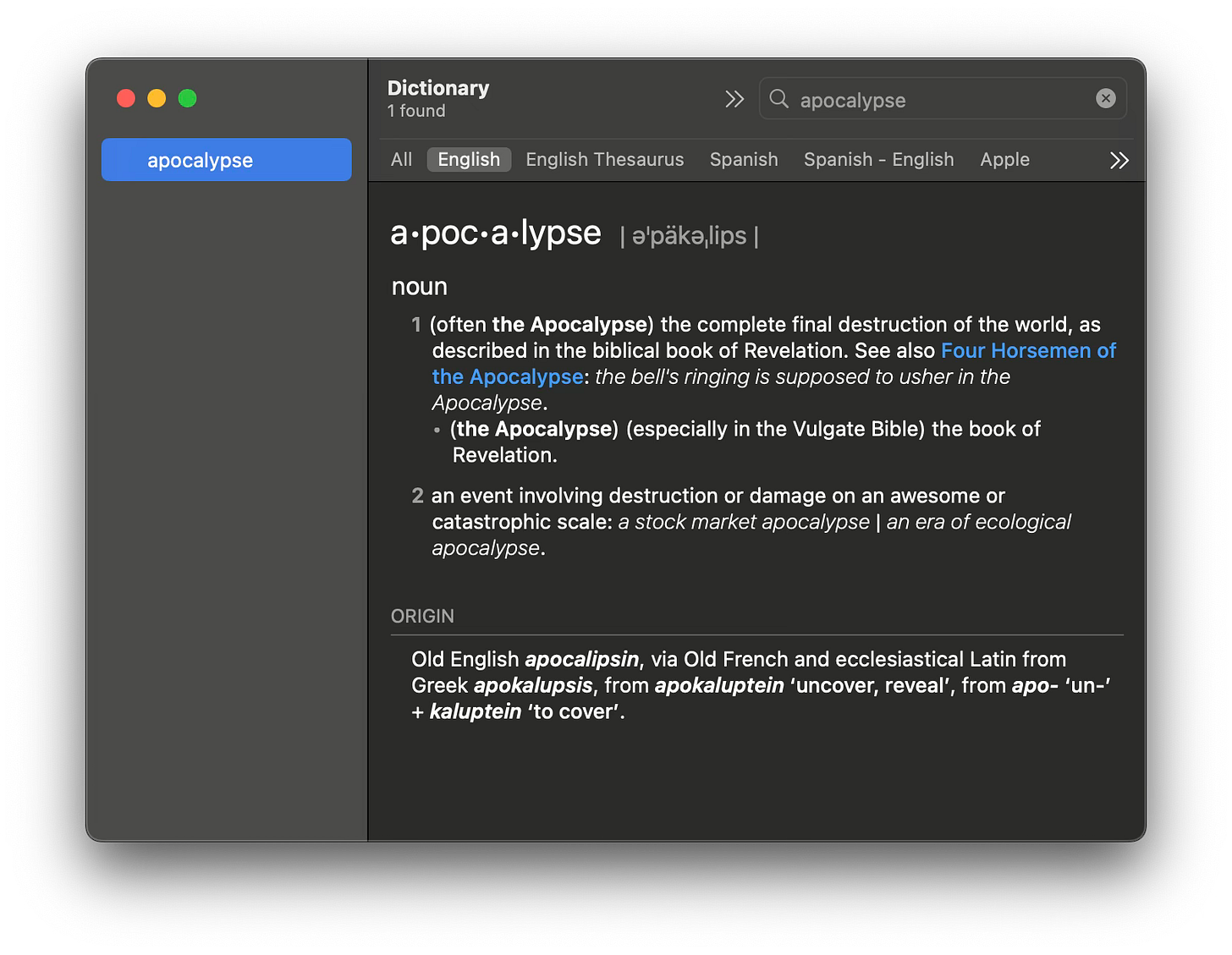

Another word that has undergone a major shift is “apocalypse.” In English, it comes directly from the Greek apokalypsis, which means “revelation.” That’s reflected in the prompt for the next discussion in the Apocalypse course from Bethlehem Bible College that I’ve been writing about:

“Apocalypse” means to reveal. Both Christ Jesus in glory and the nature of empire are being revealed in the Book of Revelation. What is being revealed about the nature of empire in the final book of the Bible?

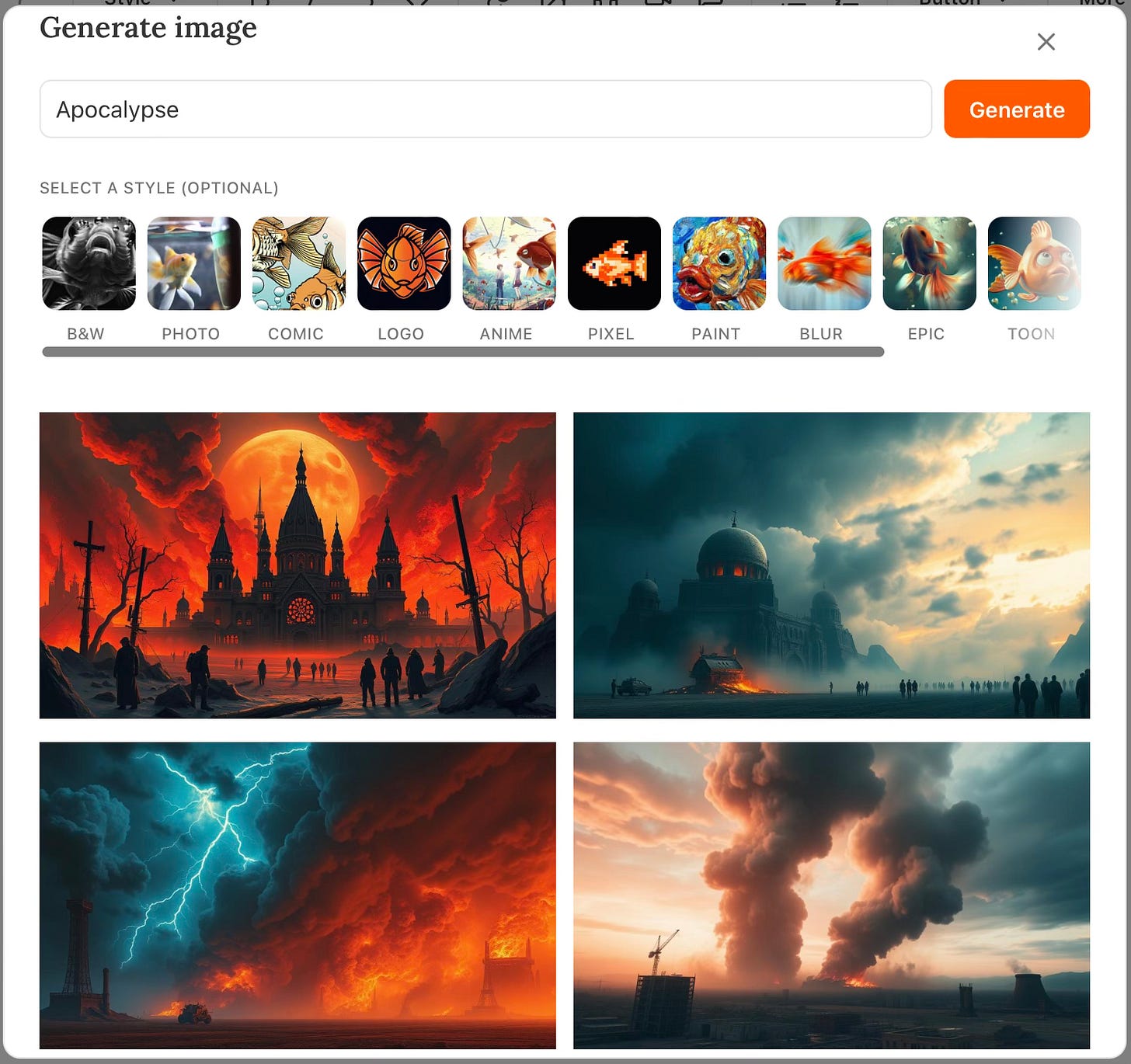

But if you search “Apocalypse” on Amazon, very few results will suggest anything like “to reveal.” Instead, you’ll get all kinds of catastrophes, zombies, nuclear explosions, etc. Even dictionary definitions now lead with disaster, not unveiling:

The Bible Project offers a better starting point. In their excellent video on the topic, they explain:

In the Bible, an apocalypse is when God pulls back the curtain to show someone what’s really going on in the world from a divine perspective.

And:

The purpose of apocalyptic is very clear: to give us a heavenly perspective on our earthly circumstances, so that every generation of God’s people can be challenged, comforted, and given hope for the future.

Because we’ve largely failed to read apocalyptic literature as apocalyptic literature, we’ve twisted the meaning of the term and the books it refers to. We’ve shifted their focus away from “a heavenly perspective on our earthly reality” and toward bizarre speculations about future disasters. “The apocalypse/revelation of Jesus Christ” becomes a puzzle about end-times events instead of an unveiling meant to shape our faithfulness here and now.

The main assigned text for the course is J. Nelson Kraybill’s Apocalypse and Allegiance. He writes:

John’s vision unveils the Roman Empire, showing it to have become a violent beast that usurps devotion belonging to God. Revelation also unveils the nature of divine love, made known by a Lamb that was slain. Humanity must choose between allegiance to the beast and allegiance to the Lamb (22).

This unveiling of empire (in Revelation 6–20) must be read in light of the letters to the seven churches (chapters 2–3). These letters show that part of the crisis is internal: some within the churches don’t even recognize how grotesque and dangerous the empire is. They don’t necessarily consider themselves hostile to God, but their allegiance is quietly drifting—likely without realizing it.

Craig R. Koester offers a helpful phrase: “ordinary empire.” He writes:

The claims of God and the Lamb clash with those of ordinary empire in Revelation’s visions. Some of John’s readers may have seen things as John did, but others would not have seen the problems with the same urgency. So Revelation’s visionary imagery must challenge them to see the world in light of the radical claims of God and the Lamb. The book takes up and transforms aspects of ordinary empire in order to show that seemingly irresistible political realities actually call for resistance, that apparently benign religious practices are actually insidious, and that glittery commercial practices can actually degrade those who take part in them.1

Revelation, then, reveals a variety of things about the nature of empire to different audiences. For some—those suffering under the empire’s boot because of their allegiance to the Lamb—it offers clarity and hope. For others—those more comfortable within the empire—it serves as a wake-up call, a warning, and an invitation to open the door to the one who is standing at their door and knocking.

As I reflect on Revelation’s message for my own context, I have to admit: my life in the US more closely resembles the comfort of Laodicea (3:14–22) than the affliction and poverty of Smyrna (2:8–11) or Philadelphia (3:7–13). That makes Revelation’s critique of empire uncomfortably relevant, and my neighbors and I desperately need “heavenly perspective on our earthly circumstances.”

Lo que la Biblia entiende y no entiende por «apocalipsis»

Algunas palabras han cambiado drásticamente con el tiempo. Cuando era niño, «spam» solo tenía un significado: era lo que comíamos cuando mi madre estaba fuera de casa en un viaje. Ahora, aunque agradezco que la carne enlatada siga existiendo, «spam» se refiere principalmente al sinfín de mensajes no deseados que llenan nuestras bandejas de entrada.

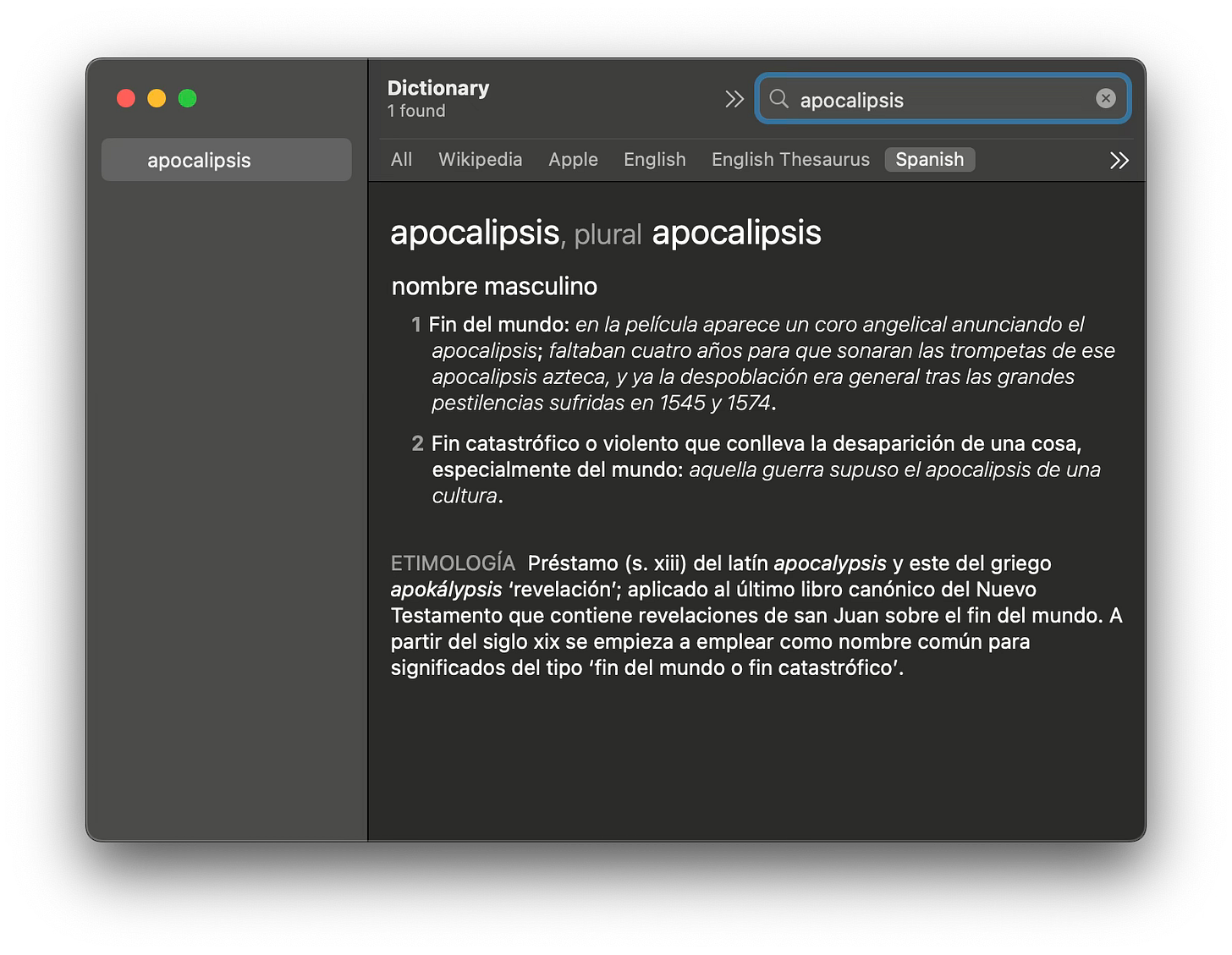

Otra palabra que ha experimentado un cambio importante es «apocalipsis». Proviene directamente del griego apokalypsis, que significa «revelación». Esto se refleja en el tema de debate siguiente del curso sobre el Apocalipsis del Bethlehem Bible College sobre el que he estado escribiendo:

«Apocalipsis» significa revelar. Tanto Cristo Jesús en gloria como la naturaleza del imperio se revelan en el Libro del Apocalipsis. ¿Qué se revela sobre la naturaleza del imperio en el último libro de la Biblia?

Pero si buscas «Apocalipsis» en Amazon, muy pocos resultados sugerirán algo parecido a «revelar». En cambio, encontrarás todo tipo de catástrofes, zombis, explosiones nucleares, etc. Incluso las definiciones de los diccionarios ahora se refieren al desastre, no a la revelación:

El Proyecto Biblia ofrece un mejor punto de partida. En su excelente vídeo sobre el tema, explican:

En la Biblia, un apocalypsis es cuando Dios abre la cortina para mostrarle a alguien que es lo que está ocuriendo desde la perspectiva divina.

Y

El propósito de la literatura apocalíptica es claro: darnos una perspectiva celestial de nuestras circunstancias terrenales, de tal manera que cada generación del pueblo de Dios pueda ser retada y confortada y reciba esperanza para el futuro.

Debido a que en gran medida no hemos sabido leer la literatura apocalíptica como literatura apocalíptica, hemos tergiversado el significado del término y de los libros a los que se refiere. Hemos desviado su enfoque de «una perspectiva celestial sobre nuestra realidad terrenal» hacia extrañas especulaciones sobre desastres futuros. «El apocalipsis/revelación de Jesucristo» se convierte en un rompecabezas sobre los acontecimientos del fin de los tiempos, en lugar de una revelación regalada para moldear nuestra fe aquí y ahora.

El texto principal asignado para el curso es Apocalypse and Allegiance, de J. Nelson Kraybill. Él escribe:

La visión de Juan revela el Imperio Romano, mostrando que se ha convertido en una bestia violenta que usurpa la devoción que pertenece a Dios. El Apocalipsis también revela la naturaleza del amor divino, dado a conocer por un Cordero que fue sacrificado. La humanidad debe elegir entre la lealtad a la bestia y la lealtad al Cordero (22).

Esta revelación del imperio (en Apocalipsis 6-20) debe leerse a la luz de las cartas a las siete iglesias (capítulos 2-3). Estas cartas muestran que parte de la crisis es interna: algunos dentro de las iglesias ni siquiera reconocen lo grotesco y peligroso que es el imperio. No se consideran necesariamente hostiles a Dios, pero su lealtad se está desvaneciendo silenciosamente, probablemente sin darse cuenta.

Craig R. Koester ofrece una expresión útil: «imperio ordinario». Escribe:

Las reclamaciones de Dios y del Cordero chocan con las del imperio ordinario en las visiones del Apocalipsis. Es posible que algunos de los lectores de Juan vieran las cosas como él, pero otros no habrían percibido los problemas con la misma urgencia. Por lo tanto, las imágenes visionarias del Apocalipsis deben desafiarlos a ver el mundo a la luz de las afirmaciones radicales de Dios y del Cordero. El libro retoma y transforma aspectos del imperio ordinario para mostrar que las realidades políticas aparentemente irresistibles en realidad exigen resistencia, que las prácticas religiosas aparentemente benignas son en realidad insidiosas y que las prácticas comerciales ostentosas pueden en realidad degradar a quienes participan en ellas.(1)

El Apocalipsis, entonces, revela una variedad de cosas sobre la naturaleza del imperio a diferentes audiencias. Para algunos—aquellos que sufren bajo la bota del imperio debido a su lealtad al Cordero—ofrece claridad y esperanza. Para otros—aquellos que se sienten más cómodos dentro del imperio—sirve como una llamada de atención, una advertencia y una invitación a abrir la puerta a aquel que está a su puerta llamando.

Al reflexionar sobre el mensaje del Apocalipsis en mi propio contexto, debo admitir que mi vida en los EEUU se parece más a la comodidad de Laodicea (3:14-22) que a la aflicción y la pobreza de Esmirna (2:8-11) o Filadelfia (3:7-13). Eso hace que la crítica del Apocalipsis al imperio sea incómodamente relevante, y necesitamos desesperadamente «una perspectiva celestial sobre nuestras circunstancias terrenales».

Koester, “Revelation’s Visionary Challenge to Ordinary Empire,” Interpretation 63, no. 1 (2009): 14.

Your explanation makes more sense to me than anything I’ve read/tried to understand about the book of Revelation. Thanks