The Senses in Which I Am and Am Not an Evangelical / Los sentidos en los que soy y no soy evangélico

Yes to six threads. No to the seventh. / Sí a seis hilos. No al séptimo.

Over breakfast, my friend said, "I just can't consider myself an evangelical anymore." I completely understood. We both wanted to distance ourselves from the baggage that had accumulated around the term. Though we belonged to different denominations, we shared the same church culture—one where "evangelical" had once been a useful umbrella term.

This conversation happened in the aftermath of January 6th, George Floyd's murder and the ensuing protests, and other cultural upheavals where "evangelical" dominated headlines. Being associated with that version of evangelicalism made me as uncomfortable as it made my friend.

But I found myself in an odd position: wanting to leave parts of it behind while also identifying with the term more strongly than ever before. My friend and I had both been shaped by the Spiritual Formation Movement, which I was researching at the time. I was growing convinced it was a movement among and for evangelicals—but evangelicals in a sense increasingly distinct from the popular meaning.

Understanding the different ways I do and don't consider myself evangelical has become both important and meaningful to me. If I had been able to think and speak more clearly in the moment that morning with my friend, I would have attempted to describe it more like this.

The Fabric of Evangelicalism

It might help us to picture threads running in two directions. The horizontal threads have to do with the emphases that make up the family resemblance of what it means to be evangelical. Many scholars have attempted to identify these, but the description that has become the standard is from David W. Bebbington. He describes four emphases:

“conversionism, the belief that lives need to be changed;

activism, the expression of the gospel in effort;

biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible;

crucicentrism, a stress on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross.”1

These four horizontal threads run across time, applying to the earliest evangelicals centuries ago, the groups in the political news headlines of our day, and to my friend and me at breakfast as we tried to figure out whether or not we were still evangelicals. However, only having these horizontal threads leaves our idea of evangelicalism incomplete because different groups over time have held those emphases differently.

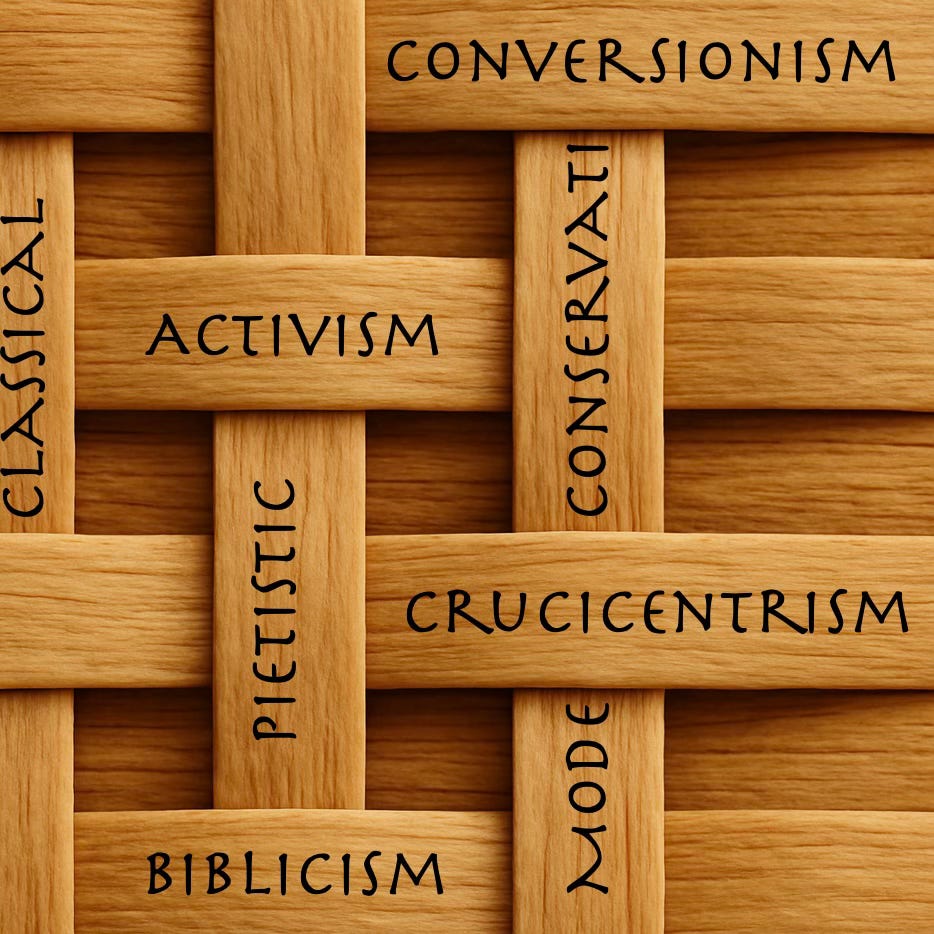

This is where the vertical threads come in––like timeline sections marking distinct periods of evangelicalism. I find it helpful to think of three main eras2:

classical evangelicalism: from the 16th century’s Protestant Reformation led by Martin Luther and John Calvin

pietistic evangelicalism: from the eighteenth century’s revivals in England and the American colonies of Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and John Wesley

modern conservative evangelicalism: the past century’s development of a conservative cultural identity intertwined with evangelical Christianity

A uniting characteristic of this last thread is its constant sense of needing to defend its understanding of the true faith from developments in the surrounding culture that threaten to undermine its foundation. In the 1920s, it sought to defend the faithful from the threat of Darwinism. In the 2020s, it is on the offensive against “woke-ism.” There have been plenty of other –isms in between, and there will be new –isms to come in future decades.

If you see “evangelical” in a headline, it is most likely only referring to this thread within the much bigger meaning of the term. No one will have to look hard for other glaring examples like this one:

Although “conservative” fits much of my friend’s life and mine, it is this modern conservative evangelicalism to which my friend and I have both resolutely said no. To the other six threads of the meaning described above, however––yes, whole-heartedly.

This framework helps me. I understand why I can simultaneously reject the version of evangelicalism that is prevalent in the headlines while also becoming more deeply grounded in the roots of my tradition before evangelicalism’s intertwining with American politics. I won’t be able to stop the trajectory of the headlines, but for others who would have fit in during our breakfast conversation, this can be a door back into an evangelicalism that feels more like home.

Los sentidos en los que soy y no soy evangélico

Sí a seis hilos. No al séptimo.

Durante el desayuno, mi amigo me dijo: «Ya no puedo considerarme evangélico». Lo comprendí perfectamente. Ambos queríamos distanciarnos del bagaje que se había acumulado en torno al término. Aunque pertenecíamos a denominaciones diferentes, compartíamos la misma cultura eclesiástica, una cultura en la que «evangélico» había sido una vez un término paraguas útil.

Esta conversación tuvo lugar tras el 6 de enero, el asesinato de George Floyd y las protestas subsiguientes, y otras convulsiones culturales en las que lo «evangélico» dominaba los titulares. Estar asociado a esa versión del evangelicalismo me incomodaba tanto como a mi amigo.

Pero me encontraba en una posición extraña: quería dejar atrás algunas partes y, al mismo tiempo, me identificaba con el término más que nunca. Mi amigo y yo habíamos sido moldeados por el Movimiento de Formación Espiritual, que yo estaba investigando en ese momento. Estaba cada vez más convencido de que era un movimiento entre y para evangélicos, pero evangélicos en un sentido cada vez más distinto del significado popular.

Comprender las diferentes formas en que me considero evangélico y las que no, se ha convertido en algo importante y significativo para mí. Si hubiera podido pensar y hablar con más claridad en el momento de aquella mañana con mi amigo, habría intentado describirlo más bien así.

El tejido del Evangelicalismo

Puede que nos ayude imaginar los hilos que corren en dos direcciones. Los hilos horizontales tienen que ver con los énfasis que conforman la semejanza familiar de lo que significa ser evangélico. Muchos estudiosos han intentado identificarlos, pero la descripción que se ha convertido en la norma es la de David W. Bebbington. Él describe cuatro énfasis:

«conversionismo, la creencia de que hay que cambiar vidas;

activismo, la expresión del Evangelio en el esfuerzo;

biblicismo, una consideración particular por la Biblia;

crucicentrismo, énfasis en el sacrificio de Cristo en la cruz.»(1)

Estos cuatro hilos horizontales atraviesan el tiempo, aplicándose a los primeros evangélicos de hace siglos, a los grupos que aparecen en los titulares de las noticias políticas de nuestros días, y a mi amigo y a mí en el desayuno mientras intentábamos averiguar si seguíamos siendo evangélicos o no. Sin embargo, tener sólo estos hilos horizontales deja incompleta nuestra idea del evangelicalismo, porque diferentes grupos a lo largo del tiempo han mantenido esos énfasis de manera diferente.

Aquí es donde entran en juego los hilos verticales, como secciones de la línea del tiempo que marcan distintos periodos del evangelicalismo. Me resulta útil pensar en tres épocas principales(2):

evangelicalismo clásico: desde la Reforma Protestante del siglo XVI liderada por Martín Lutero y Juan Calvino

evangelicalismo pietista: desde los avivamientos del siglo XVIII en Inglaterra y las colonias americanas de Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield y John Wesley

evangelicalismo conservador moderno: el desarrollo en el siglo pasado de una identidad cultural conservadora entrelazada con el cristianismo evangélico

Una característica unificadora de esta última corriente es su constante sensación de necesidad de defender su concepción de la verdadera fe frente a los acontecimientos de la cultura circundante que amenazan con socavar sus cimientos. En la década de 1920, trató de defender a los fieles de la amenaza del darwinismo. En la década de 2020, está a la ofensiva contra el «woke-ismo». Ha habido muchos otros -ismos entre medias, y habrá nuevos -ismos en las próximas décadas.

Si ves «evangélico» en un titular, lo más probable es que sólo se refiera a este hilo dentro del significado mucho más amplio del término. Nadie tendrá que buscar mucho para encontrar otros ejemplos flagrantes como éste:

Aunque «conservador» encaja en gran parte de la vida de mi amigo y de la mía, es a este evangelicalismo conservador moderno al que mi amigo y yo hemos dicho decididamente no. Sin embargo, a los otros seis hilos del significado descrito anteriormente, sí, de todo corazón.

Este marco me ayuda. Comprendo por qué puedo rechazar simultáneamente la versión del evangelicalismo que prevalece en los titulares y, al mismo tiempo, arraigarme más profundamente en las raíces de mi tradición antes de que el evangelicalismo se entrelazara con la política estadounidense. No podré detener la trayectoria de los titulares, pero para otros que habrían encajado durante nuestra conversación en el desayuno, esto puede ser una puerta de vuelta a un evangelicalismo que se sienta más como en casa.

D. W. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain (1989; reprint., Taylor & Francis, 2005), 2–3. Bullet points added / Viñetas añadidas.

My three terms here are a combination of the descriptions in Gary Dorrien, The Remaking of Evangelical Theology (Westminster John Knox, 1998), 2–3, and William J. Abraham, The Coming Great Revival: Recovering the Full Evangelical Tradition (Harper & Row, 1984), 73. / Mis tres términos aquí son una combinación de las descripciones de Gary Dorrien, The Remaking of Evangelical Theology (Westminster John Knox, 1998), 2-3, y William J. Abraham, The Coming Great Revival: Recovering the Full Evangelical Tradition (Harper & Row, 1984), 73.

You have eloquently expressed my struggle with where we find some of the people that I know and love and have worshipped with for years, but see things so differently than I do in this current political world climate. It has occurred to me that Jesus may have had a hard time teaching the disciples that He had not come to over through the Roman government, but His purpose for Redemption was so much bigger than that. His crucifixion and resurrection occurred BEFORE most of them realized what He had truly been telling them. It has made me realize how easily I can become "earthly minded" instead of keeping my eyes on Jesus and how He would be reminding me of how to treat each other through the framework of the Sermon on the Mount, reaching the marginalized and those suffering in our world today, often due to the power grabs of others, who are not authentically acting in the Name of Jesus. How can we draw others to Christ, if the Christians they see are more like the scribes and pharisees of Jesus day? My reminder of my daily "response ability" is based on Micah 6:8, "The LORD has told you, human, what is good; He has told you what He wants from you; to do what is right to other people, love being kind to others, and live humbly, obeying you GOD."

Thank you Daniel for putting non-inflammatory language to this complex issue. I have struggled with the uncomfortable truth that “my” Christian Evangelical faith has been co-opted by politics and cultural trends and no longer resembles or esteems the humble admonition to love God and love others above all else.