An American Racism Reading List

On August 12, Midland’s school board voted 4-3 to rename Legacy High School as Midland Lee in one of the saddest and ugliest public scenes I have witnessed. Supporters of the change argue that, since it is not the school’s original 1961–2020 name, Robert E. Lee High School, this is the compromise most of the public wanted when the name was changed from Lee to Legacy in 2020. Those of us who opposed this change see any use of “Lee” as inseparable from the racism in our community’s history.

There was a time I would have seen this differently. As a young adult, I thought white privilege was a made-up concept. In my past, perhaps I would have agreed with one of the trustees who characterized those opposed to Lee as the name as habitually overreacting to “micro-offenses.” Now, however, I interpret the majority’s self-professed clear conscience regarding racism as a persistent damaging thread in my community (just as the thread previously ran through me) from well before 1961 into today.

Looking back, I can identify a pre-shift that began in my early 20s, when I started to become an avid reader. At the time, I was primarily reading on theology and ministry, but even so, my old assumptions began to lose their grip as my understanding of God and the world expanded. Then, about fifteen years ago, the shift accelerated as I intentionally began listening to perspectives I hadn’t heard before and reading more broadly.

Two specific catalysts come to mind. One was a series of presentations by David M. Bailey (founder of Arrabon), in which he described “implicit racial bias.” It was both deeply troubling and freeing to realize the extent to which what he described matched my life. The other catalyst was when I was challenged to examine my bookshelves and assess how many authors came from backgrounds and skin colors different from mine. I was shocked by how small the percentage was. Those realizations launched me into a long road of repentance, listening, and learning.

Because we are in this strange cultural moment when insistence on learning our history feels like it is going against the flow, I want to share a few works that have most shaped my perspective since this shift began for me, from the oldest to the newest:

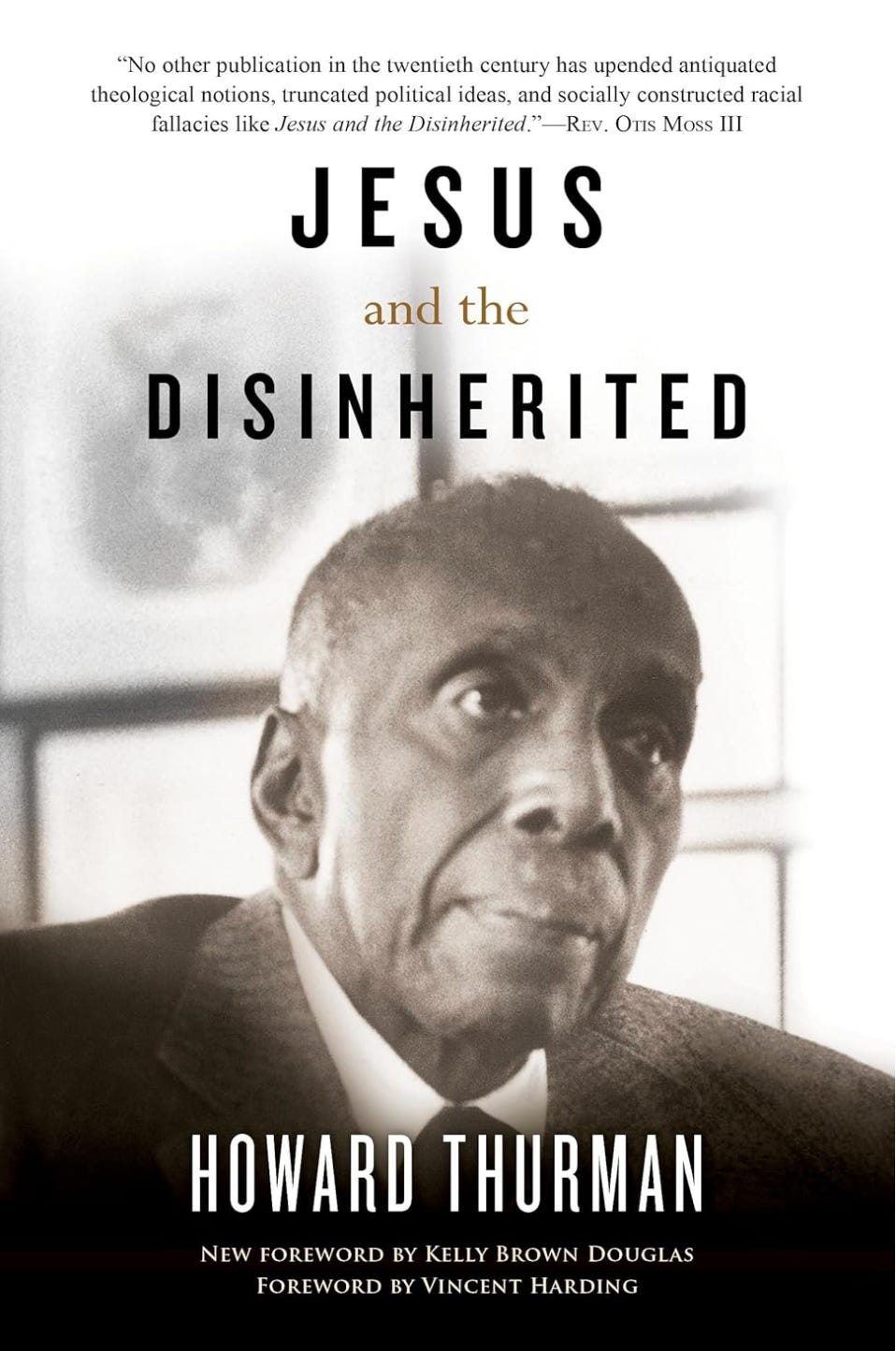

Jesus and the Disinherited, by Howard Thurman (1949): A brief but powerful classic portraying Jesus as part of a people with “their backs against a wall,” and what his way teaches about how to navigate fear, deception, hate, and love.

“Letter from Birmingham Jail,” by Martin Luther King, Jr. (1963; included in Why We Can’t Wait): King’s respectful but incisive response to white clergymen who opposed him. He shows how the attitudes of “well-meaning” white Christians were as damaging as overt racism.

“Letters to a White Liberal,” by Thomas Merton (1963, included in Seeds of Destruction): Written after reading King’s Letter, Merton expanded on the blind spots of white Christianity in his era, and his words are still fresh. From his Kentucky monastery, he offered prophetic encouragement to Black Americans and a challenge to his fellow white Christians.

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, by Isabel Wilkerson (2011): A masterfully-written exploration of the Great Migration—why Black families fled the South and the hardships they encountered in new places.

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, by Edward E. Baptist (2014): A gut-wrenching account (there were times I had to put it down and take a break) of American slavery’s violence and the economic forces that drove it.

King: A Life, by Jonathan Eig (2023): An extensive biography of Martin Luther King, Jr., showing his achievements and flaws, and highlighting his identity as a minister as central to his work.

The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi, by Wright Thompson (2024): A superbly-written exploration of the murder of Emmett Till, its role in sparking the Civil Rights Movement, the social fabric that served as the murder’s cover since the 1950s, and the persistent courage of those who have sought to tell the truth.

There are many others, but this is plenty to represent my shift. My to-read list in this area is still long—next up are David W. Blight’s Frederick Douglass and James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

Learning our history is never an individual endeavor, so: what resources have been most helpful to you?

Just finished Ty Seidule's "Robert E Lee and Me." Part history, part memoir, all challenging.

Wilkerson's follow-up book, "Caste," was also very challenging. Similar message to Erin's point from Divided by Faith, she lays out evidence that a caste system (a hierarchy in the value of people) finds a way to maintain itself even as surface circumstances (governments, laws, mores, etc.) change.

“Five Smooth Stones” by Ann Fairbairn